CONCEALED

CONCEALED

TREASURE

The $2 Art Contest has been a journey for me as both an Editor and an artist. I have learned that I must recognize my taste and bias as an artist while tempering it with impartiality as an Editor.

Choosing a Featured Artist is like cooking for a large family gathering. You have to honor where your talents lie, but you have to remember that sometimes your family just wants a turkey with traditional stuffing on Thanksgiving regardless of how good your Oysters Rockefeller may be.

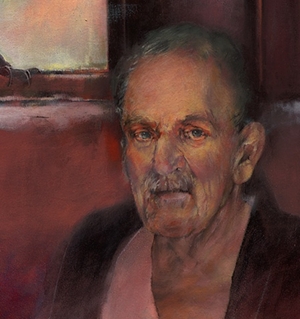

I truly have a soft spot for portraiture, as it influences my personal work; however, I also love the intimacy and vulnerability it gently masks. I find a treasure in every portrait…sort of like the pearl in an oyster as a matter of fact. During the holidays, I thought we could all use a reminder of things to be treasured–people most of all. So, Oysters Rockefeller it will be.

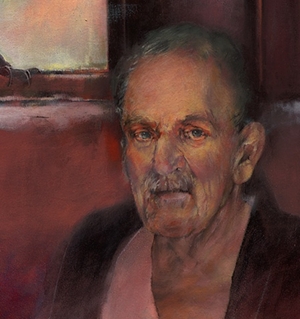

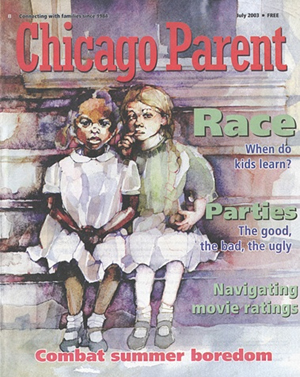

The Featured Artist chosen from November entries is Madeleine Avirov. Avirov’s work has a sadness balanced by the love and care that only an insider could have into the inner reaches of each subject. While I love her landscape and abstract work, I find Avirov’s portraiture touching and worthy of an individual audience.

The Featured Artist chosen from November entries is Madeleine Avirov. Avirov’s work has a sadness balanced by the love and care that only an insider could have into the inner reaches of each subject. While I love her landscape and abstract work, I find Avirov’s portraiture touching and worthy of an individual audience.

Avirov, studied figure painting at The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL, portraiture at the Richard Halstead Studio in Evanston, IL, and Studio Art & Illustration at Kent State University in Kent, OH.

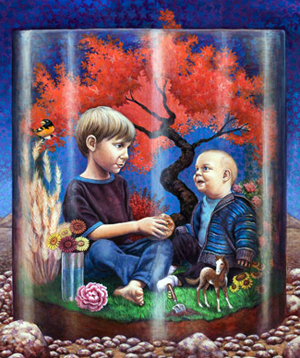

But after all this study, Avirov drew a simpler picture of her direction for me: “My subjects follow two tracks that are beginning to merge. One is darkly colored and moves backward into the past through urban terrain that Philip Roth called ‘a timeless Depression set in a placeless Lower East Side.’ Here I work with the figure as a kind of still-life element, placing my father, for example, into settings whose contents reflect and contain his particular misfortunes in order to tell a story.”

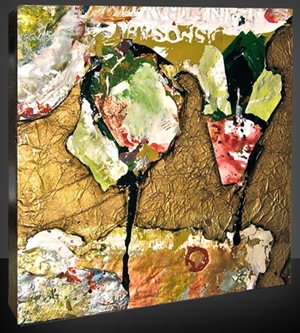

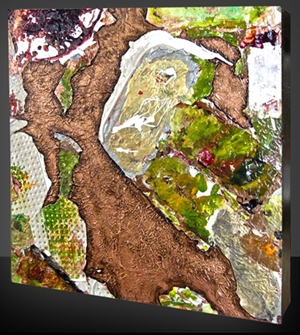

“The other track moves outward into landscape, not to replicate any particular place, but more to conjure a remembered dimension in which things are rearranged, local color is heightened, dimmed, ignored, and the surface in places remains broken and unfinished—all in keeping with a broken world.”

“The other track moves outward into landscape, not to replicate any particular place, but more to conjure a remembered dimension in which things are rearranged, local color is heightened, dimmed, ignored, and the surface in places remains broken and unfinished—all in keeping with a broken world.”

I was struck by Avirov’s process. While as artists so many of us are trying to forge our own paths and break new ground with materials and media, why would Avirov work so hard to conquer the techniques of the Old Masters? “I build up the surface of the canvas transparently—in dozens of layers in some places, in others abrading or letting the ground show through. By laying down patches of color to build form architecturally (a method I constructed from studying the texture of tree bark and from looking at Cézanne, the Spanish realist Antonio Lopez Garcia, and the English figurative painter Euan Uglow).

“First, in the same way that all genuine knowledge includes recognition—a backward glance—however interpreted, any new media or technique worth anything is in some sense built on what came before it.”

“When he was 75, the literary critic Northrop Frye understood that at that point in his life ‘discovery [could] come only from reversing one’s direction, going upstream to one’s source.’ He added ‘that at a certain point searching for the unknown gives place to trying to remove the impediments to seeing what is already there.’

“When he was 75, the literary critic Northrop Frye understood that at that point in his life ‘discovery [could] come only from reversing one’s direction, going upstream to one’s source.’ He added ‘that at a certain point searching for the unknown gives place to trying to remove the impediments to seeing what is already there.’

“I am 55, but a dozen or so years ago, I began to feel similarly compelled. There are centuries of craft, of painstaking trial and error, that have produced works I revere, and I could not reject what I had not tested for myself.”

Favorite Food? It’s either bread or fruit, the first peach of summer, warm bread on a cold day. In search of renewal and comfort, I say wearing my armchair pyschologist’s chef’s hat.

I find that portraiture can often be difficult to sell. The buying public often feels compelled to personally know the person in the art with which they choose to share their lives. When I asked how Avirov dealt with that obstacle, she answered with a straight forward pragmatism that, frankly, took me by surprise.

I find that portraiture can often be difficult to sell. The buying public often feels compelled to personally know the person in the art with which they choose to share their lives. When I asked how Avirov dealt with that obstacle, she answered with a straight forward pragmatism that, frankly, took me by surprise.

“I’ve sold far more of the work that I uneasily categorize as landscape. The short answer to how I deal with it is that, essentially, I don’t. More and more, I divide my time between writing and painting, and, lately, the months I’ve given to any one painting I’ve been giving to landscape. But even in the years when I was consumed with the figure, I did so because I could not do otherwise, and paid the bills with editing work and illustration.”

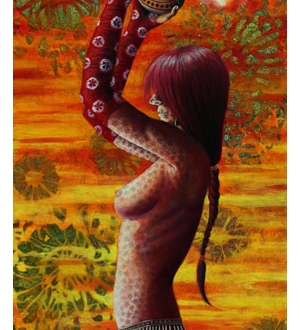

How do you classify your own work? “I also say there that it’s an ever-shifting mix of realism, surrealism, expressionism that is grounded in and is moving more and more toward abstraction, even imageless-ness. Any given work is driven by its content, but all the decisions I make about it refer to formal conventions. The story told, the emotion conveyed, are secondary even as they hover at the edge of these decisions.”

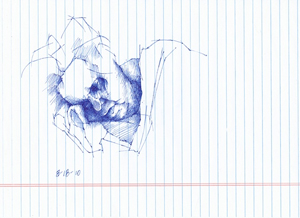

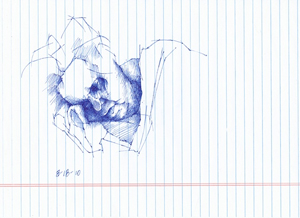

In addition to her figurative and landscape work, Madeleine is also a writer. her next big project is a book. The book’ss working title, The Hippocratic Face, refers to Hippocrates’ description of the appearance of the dying. See work of the same name pictured right. It was conceived as a consideration the 90-year-span of the artist’s mother’s life in the light of her final days and weeks, in the hospital and in hospice, as well as an examination of the cultural obsession with extending life against all reason.

In addition to her figurative and landscape work, Madeleine is also a writer. her next big project is a book. The book’ss working title, The Hippocratic Face, refers to Hippocrates’ description of the appearance of the dying. See work of the same name pictured right. It was conceived as a consideration the 90-year-span of the artist’s mother’s life in the light of her final days and weeks, in the hospital and in hospice, as well as an examination of the cultural obsession with extending life against all reason.

Thank you Madeleine for sharing your work with us.

I felt a little like an eavesdropper in the hallways of your life while reviewing your work. It was a privilege to be granted such an intimate view.

Want to be a Featured Artist on www.ArtAndArtDeadlines.com?

Check out the $2 Art Contest!

NOTES for NOODLES

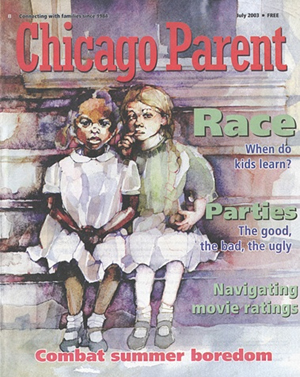

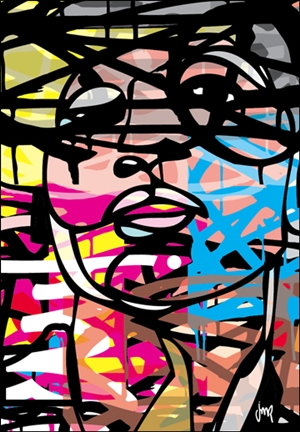

NOTES for NOODLES Thousands of visitors come to Austin in March and music fills almost every street and corner downtown. Studio2Gallery is seeking visual artworks to offer tribute to musical artisans – to the music and the people who make it happen.

Thousands of visitors come to Austin in March and music fills almost every street and corner downtown. Studio2Gallery is seeking visual artworks to offer tribute to musical artisans – to the music and the people who make it happen. DEADLINE: Entries must be received by February 14, 2011.

DEADLINE: Entries must be received by February 14, 2011. Ladd has been an instructor at the Rocky Mountain School of Photography and is a member of the Texas Photographic Society.

Ladd has been an instructor at the Rocky Mountain School of Photography and is a member of the Texas Photographic Society.